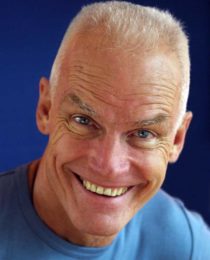

Transmission in Tibetan Buddhist Practice. Meditation. Part II

by Lama Ole Nydahl | Issue 27

In November 2009 Lama Ole Nydahl took a weeklong road trip from Minneapolis, Minnesota to Chicago, Illinois. The occasion was the tenth anniversary of Diamond Way Buddhism’s activity in the upper Midwest of the USA and the inauguration of the Heartland Retreat Center in western Wisconsin. During this trip Lama Ole gave three “transmission talks” to his students, framed by the three pillars of Buddhism: information, meditation and activity. The text presented here grew out of the second of these talks. The first transmission text was presented in Buddhism Today 26 and the last text will be presented in the next issue.

Buddhism consists of three pillars for our growth and realization. As should be expected, the first one is correct information—not things to believe but facts to understand and check. This is essential because we must know what brings the results that we want and what has unpleasant effects. Then follows the pillar of meditation, where we take what is valuable to our situation from the head into our heart and practice it. Finally, we have to avoid obstacles on the way, living and practicing in ways that benefit others and ourselves. This is the pillar of activity.

This overview is useful in Western cultures and permits a different approach from what was available to practitioners in Tibet. Most Western meditators today have a broad education. This means that we have a humanistic background and think clearly about political and other matters. Even for those who do not care, it is difficult to avoid at least the most basic information. Most enjoy thinking that at least something in their lives is meaningful.

The Tibetan situation was different. Most people were self-taught, had few choices, and—especially in the monasteries of the state church—education mainly consisted of learning books by heart, which then became the source of debates (just like in the Middle Ages in Europe). Their path to transcendence was devotion to lamas, who were often exceptional. This should explain some of the mysterious points brought forth during today’s exciting meeting of two so rich and different worlds.

The first pillar, the pillar of information, is mainly for removing wrong ideas. Its ultimate basis is the understanding that space is non-local information, that we therefore all have Buddha-nature and that the very essence of anybody’s mind is already—and always was—enlightenment. This is difficult for many to understand, but it means that no Buddha can add anything to our mind. What a Buddha does is remove the veils that keep us from recognizing this essence. It has been proven in philosophical, psychological, and even purely scientific experiments that space contains insight, that it is a container of all and not a black hole between objects and events. Our scientists talk about “now time” which means that, at all times and places, the same knowledge is present. We may have noticed that some Nobel Prizes were split because people in different countries, who did not know one another, came to the same conclusions at the same time. There are countless examples daily, baffling unprepared people…how did they know?

Buddha describes this phenomenon forcefully: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form, form and emptiness cannot be separated.” This is also proven by top scientists at the multi-billion-dollar Large Hadron Particle Collider near Geneva, Switzerland. Here, they managed to create 100,000 times the heat of the sun’s center and still didn’t find any “Higgs bosons” (particles) which could prove the material world to be real. Also, much earlier, they discovered that “virtual” particles appear in total vacuums, which proves Buddha’s second point: “Emptiness is form.” That they cannot be separated is, therefore, also proven.

Buddha, aiming to share his experience and set free all aspects of human beings, taught two kinds of emptiness to remove mind’s two veils. First is the emptiness—non-existence—of anything personal as lasting and real. Explaining that bodies, as well as feelings and thoughts, are constantly changing, that only the consciousness knowing them is always and everywhere—mind’s awareness which is the same luminous space in everyone—he helped them avoid any victim-role or feeling like a target. Having thus liberated his students from the “me-you” basis for disturbing feelings, he went on to attack their stiff ideas, bringing them to full enlightenment beyond the constraints of materialism and nihilism.

For most, this second point, although further away from the realm of blinding emotions, may be more difficult to understand in its fullness. That it is a serious matter is, however, illustrated by the catchy statement by the great Indian Yogi Saraha 1,200 years ago. He put it in this way: “People who think things are real are stupid as cows, but those who think they are not real are even more stupid.”

And what does that mean? Simple. If things are real, so are old age, sickness, and death, meaning pain. If we think they are not, however, we get these troubles anyway. In addition, we will make basic mistakes and hurt ourselves unnecessarily.

And what is Buddha’s solution? Elegant, as always. He tells us that the world is a collective dream, condensed from the limitless potential of space through our karmas, and now experienced through the colored glasses of our changing mental states. Recognizing this, he advises us to go for the “good” dreams that unleash mind’s limitless qualities and stay away from any “bad” motivation which will eventually bring problems with society or necessitate psychiatric care. The disappearance of both veils is the ultimate perfection called enlightenment.

Even though all beings contain this radiant space till the moment of death when they are usually unprepared to use it, very few grasp its richness—being fearless because space is indestructible, joyful because it plays in so many and ever-fascinating ways, and kind from noticing that the others are countless and oneself only one. Thus, doing something for them is more important and should be self-evident to all, but remains a rare perfection.

Such “emptiness” may be approached less or more fully. Under the all-pervading discipline of Tibet’s vast “Yellow Hat” monasteries, it was natural to take an analytical view of the subject. One observed outer and inner phenomena critically and found them to be empty of any lasting substance or self. The term for this is rang tong. Lay people in the midst of life and the practical thinkers of the three “Old” or “Red Hat” schools add the “experiencer” to this, although that has no inherent nature. Life would be too limited without that. It is called shen tong, “empty” and “something more,” the “more” being mind’s capacity for awareness.

Finally, what aspect of realization do the accomplished lamas of these experience-based lineages highlight? What is transmitted through blessings and initiations into the united buddha forms? They use the word de tong. De comes from dewa (bliss) combined with tong (empty). It means that the experience of mind’s inherent and constant power is beyond any obtainable conditioned joy and that the radiance of the mirror is timeless and beyond any object, even the most pleasant, which may appear in it. For Diamond Way Karma Kagyus, this essential state, transmitted for 1,500 years in India and 950 in Tibet and now passed on to our hopeful West in essential and readily accessible ways, is now our treasure. It is the greatest of gifts, must never be forgotten, and should be known before practicing that middle pillar of meditation.

In Tibet the central pillar of meditation was the main thing to the “old” schools and the dimension of transcendence was even deeply imbedded in ordinary language. However, the long periods of meditation mentioned—which may turn practical Westerners off—are not as threatening as they may look. Much of the time went into acquiring necessary knowledge. It was really school-time and comparable to the periods we spend on education and re-training throughout our lives in the West. The extreme sensory deprivation of closed retreats in caves, which the life stories of highly realized lamas recount, will be for the extra hardy and motivated after our transmissions and lineages are well established in Western free countries, and then with health care and daily vitamins!

Although some manage to make it look very complicated, Buddhist meditations are actually quite simple. All consist of two steps: one focuses on the quality one wishes to obtain and then accomplishes it. This covers the whole range, from seeking a peaceful distance (Theravada) to developing compassion and wisdom in balance (Great Way), to the ultimate teaching—behaving like buddhas until we become buddhas (Diamond Way). One’s practice on the first two levels should be precise with no emotional restrictions. On the Diamond Way, one’s realization and power to pass it on depend fully on one’s thankfulness toward one’s teachers and the transmission. Here this quality is decisive. All methods were given by the Buddha for different people, and are fine tools for fulfilling meaningful goals.

All stages and ways mentioned above are included in a Diamond Way meditation on a buddha form, or on one’s lama as the essence of all buddhas. Therefore, describing its steps, views, methods, and effects gives an overview of the vast and exciting subject of Buddhist meditations. Complete on every level, it is probably the most used Buddhist meditation in the Western world today.

One begins by emptying mind of whatever confusion or strong feelings it may contain. Feeling or counting one’s breath at the tip of one’s nose quickly brings this about. Some may focus better on an object but that is done later in the meditation. After an initial counting of twenty-seven breaths has filtered the day’s event from our body and mind, we are inspired through four eye-opening thoughts:1) that only mind feels happiness while most beings seek it in outer things; 2) that we should look for it now, not knowing how long we will live; 3) that what we do, say, or think will become our future; and finally, 4) that there is no greater perfection than enlightenment and we benefit nobody when in pain or confused ourselves.

At this point, even a hero would look for something trustworthy, and what is unchanging, always, and everywhere? Space. It is not a black hole or a lack of anything; it is the very root of everything outer and inner. As we already saw, knowing that one’s awareness is no “thing,” one becomes fearless. Seeing the free play of that space, one becomes joyful and rich and, recognizing that it is shared with all beings, one becomes kind. This full development, called Buddha, is one’s absolute refuge. Being practical, and wanting that experience, one looks for ways to obtain it. Here, Buddha’s teachings have no other goal. He does not have a foot in two camps, trying to push the commandments of some god down over our heads, but only aims to show us our own enlightened essence. Such teachings are known as dharma or “the way things are.” Furthermore, because getting the right information and finding out how to use it practically is time-consuming and very difficult, he started sanghas—groups working with the aspects of his teaching that fit their capabilities. For the highest of these levels, including all aspects of body, speech and mind, he praised the lama as their embodiment and the necessary teacher. The lama should uphold the lineage he represents and transmit its human warmth. This is called blessing. Equally important, he should give methods for uniting with the buddha forms that express mind’s enlightened qualities—yidams—and finally, he should be so honest and politically incorrect that the protectors haven’t left him in disgust. Then he can also transmit their energizing power. Having opened up to such absolute qualities, hopefully with the motivation of using any progress to benefit others, the meditation stops being linear. From here on, it utilizes all capacities of body, speech and mind for identifying with perfection.

Here, the power field of a buddha form is involved. In the Diamond Way it is mainly the 16th Karmapa. Since 1110, the Karmapas are the first incarnate lamas of Tibet. Considered the king of Tibet’s yogis, the Karmapa manifests in the position of holding the Black Crown over his head and invoking the Buddha of Compassion for all.

After receiving the clear light for one’s forehead with the vibration OM, the transparent red light for one’s throat with AH and the transparent blue light for the heart center (central chest) with HUNG, singly and then together, one uses the mantra Karmapa Chenno (activity of all buddhas, work through us) for as long as it feels right. Finally, the lama dissolves into light. It falls on us, spreads everywhere and dissolves everything. We rest in this centerless, uncontrived space for as long as mind stays fresh and then we bring forth the pure realm in which we wish to live. Here all beings have buddha nature and every atom vibrates with joy and is held together by love. All sounds are mantras and even the clumsiest thought is wise, simply because it can happen. Holding this view to our best ability until we can again enter into absorption, and knowing beyond doubt that highest joy is highest functioning and truth, ultimately there will be no difference between formal meditations and the periods between them. All beings are buddhas in a Pure Land. (If you are intrigued by this meditation, please learn it from a Diamond Way group or teacher and get the text at your nearest Diamond Way center.)

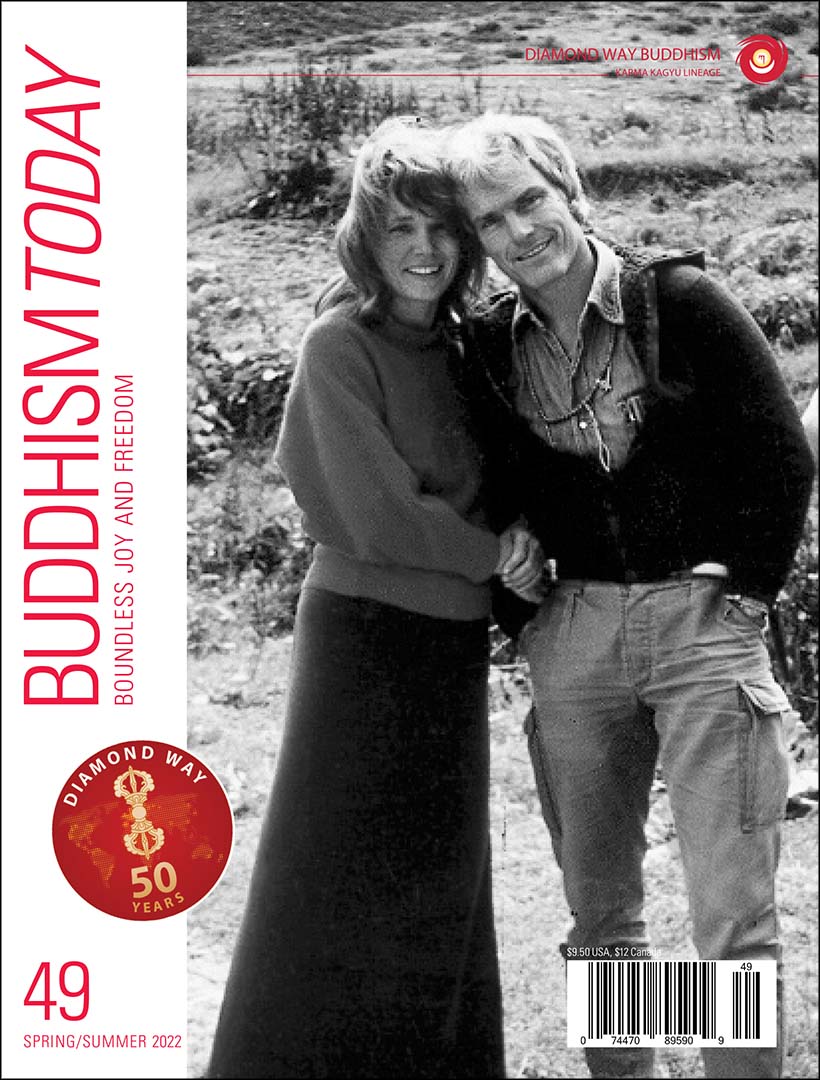

Recently California and the Midwest have obtained and are working on truly inspiring retreat centers, with the northern East Coast and Texas hopefully not far behind. Here are some words about the Diamond Way practices which will be done there. The methods my wife Hannah and I received in the Himalayas between 1968 and 1972 and during six months in 1983, including the ones given by lamas we invited to our Western centers or visited in the East with friends, are certainly unique and exceedingly effective. Even though there are only six million Tibetans (as compared to the billion other Buddhists in the world today) and many are refugees, they have still produced the most well-known and varied Buddhist teachers.

Practicing to open mind’s potential is like betting successfully. Here one cannot lose. The more one wagers, the greater one’s gain will be. If one mainly aims for a peaceful life, creating a distance to disturbances and developing an acute awareness of causality are enough. If one goes a step further and activates one’s inherent compassion and growing understanding that the world is actually a collective dream seen through the colored glasses of one’s own mental state, one’s bet and gain are much higher. Here, one’s inner life and idealism are involved which vastly increases the effect. However, if on top of this, we dare to have ultimate confidence and behave like a buddha until we become one, courage, fantasy, attraction, devotion, thankfulness and all other fine and intuitive qualities spring forth. Realizing that we can only imagine enlightenment elsewhere because we already have it inside, that space and information are inseparable, and that we are therefore all buddhas who have not realized it yet, our world becomes an exciting place and bringing oneself and others to such heights of awareness remains a constant source of fulfillment.

The outer frame of Diamond Way meditations is already deep psychology. It influences body, speech and mind in beyond-personal ways through enlightened feedback from the peace-giving, enriching, fascinating and powerfully-protective buddha forms and their mantra vibrations. Masters of Diamond Way meditations see our energy as a horse and our awareness as its rider: they should complement and influence one another in ultimately meaningful ways, bringing the above-personal qualities to full fruition wherever possible.

Thus, our friends who primarily hold a hammer and those seen with books or beads—and hopefully all get a chance for both—will discover the blessing we establish at our retreat centres. The blessing is this: that no finer and more meaningful endeavor exists than giving others and ourselves the conditions for opening up to our potential. All that hard construction work, as well as the cleaning of obstacles especially through the first two preparatory activities of Ngondro, is a gift for one’s whole life. Body and speech here change from difficult masters to pleasant servants and friends and the certainties and blessings, which thereby arise, remain a lasting confirmation and gift.

So, with much said, here are the practical points which were your original questions: What to do in a retreat? And who can do it? If one has robust life experience like our Heartland friends, a high level of discriminating knowledge due to the many, diverse, and politically correct influences on Buddhism from groups and universities in the East, or has cleared one’s path through the confusions of New Age, Hollywood, hippiedom and enormous numbers of nationalities whose languages and cultures one does not understand, like our friends from the sunny West, one is stable enough to do retreats.

I advise beginning solitary retreats in a relaxed way, with four daily periods of meditation, starting early when mind is more clear and with enough time for also reading books of our Karma Kagyu lineage (others are also good), while avoiding confusing practices and terminologies or reading for exams or education. Nobody can meditate all the time, anyway, and the world is waiting. You may eat in the same room as others, but should avoid speaking to them and, above all, looking into their eyes. Thereby you get on their trips, which is not the idea during retreat. Keep constant awareness that every purification is a liberation and every moment of insight, understanding, or bliss is a gift to be later shared with others. Whatever may come up, what is aware of it is our true essence, our timeless and indestructible buddha nature. Meditators should, therefore, always stay with the positive view, and avoid making a part of their minds into a policeman, comparing and checking the details of what is going on. The space-awareness between and behind the passing impressions is what we want to know.

This was some general advice concerning the practical aspect of retreats. Once a strong development starts, however, also in daily life one will experience something like an inner retreat. Many habitual games and distractions here lose their interest because so much of mind’s power stays active with one’s inner world, clearing out obstacles and other causes of future pain. It establishes formerly uncharted, stable and beyond-personal values, and discovers and opens up new mental territory. While one’s karmic impressions are sorted out, life becomes fresh and former downs become sources of strength when helping others. Then every event is a teacher and manifests the unlimited quality of mind. As unshakeable qualities evolve, one increasingly becomes a refuge also to others.

In the outer practice of retreats we thus establish what should be done and avoided. In our inner practice we follow the stream of instructions given, conscious of what is taught and experienced, cleaning out doubts. As expectation and fear thus dissolve, suddenly and in moments without expectations, this becomes mind’s secret and absolute state of naked awareness. Beyond any artifice, one recognizes oneself to be fearless, experiences richness and spontaneous joy, and looks in wonder as one’s body and speech know and do so much that is clearly beneficial.

So that is the transmission through meditation. We may be in different lanes but are all on that same way.

If you have any questions that would be good.

Question: What do you mean by “digging deep”?

Lama: “Digging deeply” means getting beyond the habits and confusions that are usually clouding one’s mind, getting underneath them and being the experiencer itself. It’s identifying with that which is looking through our eyes and listening through our ears and being conscious.

Question: Why do you advise involving the rational aspect between the sessions? Why is that important?

Lama: Well I think it’s good because mind should be developed in a round and total way. If you don’t have anything you need to study and no exams to pass, or something similar, of course then it is most useful to inspire oneself with the life stories of our ancestors in the lineage and maybe check out Entering the Diamond Way and Riding the Tiger, which are our history in the West. They are important when you want to represent us. If you have something related to some work that you are doing in the world, however, then I think it’s okay to use some time when you couldn’t meditate anyway for doing that. It won’t destroy the depth of our meditation. It even harmonizes many by using additional aspects of mind. Mind is a beautiful thing; it can shine in all ways and directions. So, if you want, you can do this. You can think very well while not meditating in retreat.

Question: What would you say should be the minimum number of days in a retreat?

Lama: I think three days, like a prolonged weekend, would be good for everyone. If you have some qualities you want to develop, some things to clean out, some realizations to size up or make happen, I would say a focused long weekend can already make an imprint or set a course. We have one woman in Austria, a mother, who every week gets one day off from the family. The father takes care of the child, and then she goes for twenty-four hours in a closed retreat. This is an amazing idea.

Question: Why do you advise involving the rational aspect between the sessions? Why is that important?

Lama: Well I think it’s good because mind should be developed in a round and total way. If you don’t have anything you need to study and no exams to pass, or something similar, of course then it is most useful to inspire oneself with the life stories of our ancestors in the lineage and maybe check out Entering the Diamond Way and Riding the Tiger, which are our history in the West. They are important when you want to represent us. If you have something related to some work that you are doing in the world, however, then I think it’s okay to use some time when you couldn’t meditate anyway for doing that. It won’t destroy the depth of our meditation. It even harmonizes many by using additional aspects of mind. Mind is a beautiful thing; it can shine in all ways and directions. So, if you want, you can do this. You can think very well while not meditating in retreat.

Question: What would you say should be the minimum number of days in a retreat?

Lama: I think three days, like a prolonged weekend, would be good for everyone. If you have some qualities you want to develop, some things to clean out, some realizations to size up or make happen, I would say a focused long weekend can already make an imprint or set a course. We have one woman in Austria, a mother, who every week gets one day off from the family. The father takes care of the child, and then she goes for twenty-four hours in a closed retreat. This is an amazing idea.

Question: What advice would you give for when we come out of retreat?

Lama: After every Diamond Way meditation it’s the same: Keep the highest possible view! You are in Buddha’s pure land, so stay there! This is not different when one comes out of a retreat. Even though worldly situations appear and you must act, you should keep the highest level and view. You see everybody as having Buddha-nature, you hear sounds as mantras, you see thoughts as at least interesting, and you experience ideas and whatever happens as mind’s free play. The main practice in Diamond Way is to never actually leave the pure land. You never leave it; you stay in it as well as you can. Every time you go down a bit you say some mantras, meditate some more and melt together with the lama or Buddha and remember that it is there. In the end, wherever you go, you will see something interesting, hear mantras, feel joy, and have all kinds of blissful experiences. Always remember that highest truth is highest joy. The more perfect, meaningful, radiant, and the more beautiful we see things, the closer we come to their real nature. That’s the important thing. It is for the heart of Diamond Way practice to know that.

That’s why, instead of a very few long meditations, I always advise many short ones. Like when the boss is out of the office and you have a couple of minutes, you let the Buddha dance from the top of your head into your heart and fill you with light. You hold your papers in your hand and when you hear the boss on the stairs again, the Buddha disappears in space, promises to be with you all the time, and you are back to work again—with a smile!

Question: And when meditating together?

Lama: Hannah and I always did that, so also the nights were joyful! One should always enter with an equally mature partner. If both have the same motivation, love each other and know that every moment of unrelated talk is a leak in one’s realization, one will even motivate one another and share more and better afterwards. Meditations are deep and wonderful things to share.