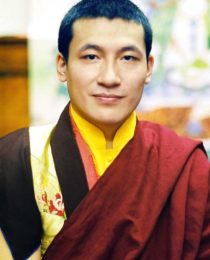

Timeless Wisdom Meets Modern Technology: Karmapa on Facebook

Social media, with its unparalleled power to instantly connect people across the globe, continues to play an increasingly significant role in the world today. Recently, His Holiness the 17th Karmapa Trinley Thaye Dorje invited his 140,000 Facebook followers to ask dharma questions via his Facebook page. In response, his page received a multitude of questions from students all over the world. We are happy to republish a selection of these questions, along with Karmapa’s thoughtful and practical responses.

Why is it so important to have a spiritual teacher if we have all the answers within ourselves and have the faith that we can practice the dharma on our own?

We all have innate, unborn qualities. That is not to say that, in a Buddhist sense, we are already enlightened, but the seed of this potential is planted inside each and every one of us. It is inherently present.

To really sit down and tell ourselves things such as “I am inherently pure and decent,” can be difficult even though we can relate to these truths during unemotional moments. But if we have a hard time accepting these truths when we are in crisis and have doubt in ourselves, then this is a clear sign that we do need someone to guide us, someone to show us, someone to explain and teach us what it is, and that it is like that.

In terms of the question of whether we need a teacher or not, it is not that we have to go to the end of the world to really find the answer. I believe it is right here, right now. We can just ask ourselves individually, “Do we really have the potential or not? Do we really understand the truth?” Or, we can change the terms by saying, “Do I know the nature of mind? Do I know the universe and phenomena?” and so on.

For this, we may need proper guidance. And then, of course, there come many questions such as “How do we find an authentic guide?” and “How do we know that this is the right path?” and so on. For that I think it is important to focus on the basic qualities of the teachers or guides and also use our own basic qualities to assess with a good degree of clarity, i.e., without emotion. So, whether Theravada teacher or Mahayana teacher, there are certain standards or certain basic qualities that he or she should possess in order to guide.

Your Holiness, what should I say and how can I help my mother who is dying of cancer?

I believe that when anyone is in this kind of condition—be it cancer or any other form of illness—in these difficult moments, I think there is only one thing that we can provide. In fact, we can provide this, not just during difficult times, but also when things are seemingly all right. What is this thing? It is our countless inner qualities.

Now, in this case, providing emotional support is priceless. It is the best; there is nothing of greater value. At such a moment, whatever amazing things we can provide materialistically will not help at all. At such a moment, power, fame, or material wealth don’t matter. Instead, that simple gesture of emotional support goes a long way. It is everything. This is particularly true when it comes from someone you know, for it is easier for the recipient to accept.

There are cases, of course, when a stranger gives that kind of support, and this also helps. However, in the case of the person asking the question, I think the best thing you can offer is the time and energy to give emotional support. Even if it is challenging, it may be beneficial for you to appear and express in front of the patient that you are all right; that you are strong and you are confident—confident that everything will be alright—and then of course also express this through verbal and physical gestures.

Then, I think there are some cases where the patient may become cured. But even if they don’t, at least they will be able to go through that journey in a much more peaceful manner.

Yes, these are the things that the buddhadharma can always provide.

Finding Balance: realization of impermanence is an important part of building the motivation to practice. However, lay persons are mostly still caught up with work and family, and there is little time left for dharma study, inner reflection, and meditation. Should we consciously try to limit the time spent on work by getting a less hectic job and trying not to get married, which will increase family commitments, just so we have time to practice? Practice I feel is very important, but if we continue to live on beyond our next breath, bread and butter, family and friends are also important. The current day and age does not allow us to be like Milarepa and be so extreme as to survive on nettles alone. What is your advice to us lay persons on how to balance practice and our mundane lives?

First of all, we have to be aware of the value of practice. I think the person who asks this question seems to understand the value of it.

For other readers, in order to decide how to balance such things, and also to understand the answers, I think it is important to know the value of buddhadharma.

Knowing the value of buddhadharma is deeply connected with knowing the value of other people and the connection with them. Now in this case, the person asks about family, which is directly related to buddhadharma. So in some ways, the idea of separating family time and time to practice is a little bit more complicated than it first seems.

First of all, one has to really understand the value and meaning of the buddhadharma. The next step is to ask the following question: “What can I do, according to where I am right now, according to my own circumstances, and my own time?”

This question is all about managing time, so again we may ask ourselves, “What can I manage?” Of course, we have to look at it quite realistically in terms of what is manageable, and also in terms of what is necessary and what is unnecessary. There may be a lot of things that we spend our time on that are quite unnecessary, and I think we then have to find the courage to be able to somehow slowly, slowly let go of these unnecessary activities.

These could vary from one individual to another. For some, maybe painting is beneficial; maybe it is a way to somehow benefit oneself and others. For others, it might be a complete distraction, so accordingly we have to see. What is required is an honest exploration into what can be done, what can be managed, and what is necessary and beneficial.

So I think if we cover these areas, then we are able to challenge this idea that there isn’t enough time. Indeed, just by going through these questions, we are actually making time—we are already making progress. At the very least, we develop a deeper understanding of our situation.

Once we have covered these questions, then I think we are left with the last step. This is to plan our life so that we are able to do everything that is necessary and beneficial. In this case, we have to make time to practice, we have to make time for others, we have to do everything, and somehow make it quite balanced—equal. It is difficult to find this balance, but it is important to plan in this way. It is also important to remember that the buddhadharma reaches into all aspects of our life and experiences, and our connections with others, so in some ways every moment is also an opportunity to practice and to find balance.

As a parent I am terrified for our children and the world we are leaving them. Global warming suggests that one day the earth will be uninhabitable. Governments seem too slow and in some cases unwilling to act for change, so how can Buddhism help us to avert this crisis?

That’s a very good question. Of course global warming is a real issue but, from time to time, I feel that maybe the idea of this threat is a little bit overused. When this threat is overused, it can lead to the feeling that there is very little an individual can do, which is not beneficial or true.

What is needed is the knowledge about what each of us can do in any situation, and I believe Buddhism has a very important role here.

In this context, ‘knowledge’ is not just a vague term, but refers to something very particular: the knowledge of our inner qualities—our inner knowledge. In other words, it is a type of knowledge that helps to unlock a hundred doors at the same time. This is the intention of the buddhadharma. In this sense, I think we are already in a beneficial position to address all kinds of challenges.

When we think of knowledge in more general terms, the usual method and form that it takes is education. If we leave aside the Buddhist part for a moment, I think that in many cases around the world, the emphasis on education today is much better than previously in history. There are, of course, still challenges faced today but, in many cases, where there was previously an absence of opportunity for education, now there is an abundance. In fact, there are so many education opportunities in some parts of the world that sometimes there is a problem of not knowing which route to take, a problem of choice.

As knowledge is what is required to tackle global warming and other challenges, I believe that education provides a very good platform for this knowledge and potential to be cultivated.

Education from a Buddhist point of view—what I would like to call inner wealth, the unborn qualities that we all have, and which I already mentioned in my first answer—is about cultivating knowledge and qualities that are already there. No one had to teach them to us, no one had to open our eyes or expose us to anything like that. Somehow, these qualities are naturally there, such as being kind, being generous, being understanding. One could even say these are the most basic of qualities.

These are the things that I think we need to tap into, and I think that is key to what Buddhism can offer. Ever since our historical Buddha Shakyamuni taught the buddhadharma, these were his very first words and also more or less his last words too. And ever since, the buddhadharma that we have been practicing over the centuries and millennia has always been about cultivating our inner qualities. And whoever has understood this point has lived an amazing, extraordinary life. Whoever they touched, whoever they met, whoever they spoke to, there was always a benefit.

One great example would be that of Milarepa. If we just look at his life story we can see that whoever he met, whatever the context, after that meeting somehow there was always a benefit, even from simple accidents.

So I think that, in terms of overcoming global challenges, Buddhism has a great deal to offer. The platform is already there, the methods to cultivate our inner wealth, and so all we need to do is just act upon it.

But how?

In this very moment, this very space that we have right here, right now, there is an opportunity. This moment for us is the center of the universe, nowhere else. So here, and now we can already start doing something. In other words, the buddhadharma provides us the important knowledge and understanding about what each of us can do in any situation. There is somehow no need to feel helpless or hopeless because each of us can do so much.

In this case, the fortunate thing is that we hardly have to move a muscle to achieve so much. We just need to focus on recognizing what these inner qualities are, or what this inner wealth is—just by sitting. Buddha found a way where we seemingly need to do hardly anything. Whatever we’re doing, whether we are sitting, talking, or even sleeping, we can activate and cultivate these inner qualities of wisdom and compassion.

If we can follow in the footsteps of Buddha, then we will be able to stop global warming, ice age, stone age, everything—all in a single sitting.

My question is about pure view and the ability to discriminate. If one practices pure view of everyone, would it inhibit our ability to judge people and function in daily life? As the Buddha is omniscient, and we are aiming to reach the same wisdom of knowing everything exactly as it is, why should we “superimpose” a pure view on something that we know to be a fact? For example, if someone has certain faults, is pure view about wiping away or ignoring these faults rather than having an accurate assessment of that person?

In a Buddhist context, the longer we spend on the path as a practitioner, the more important it is to explore the subject of pure view.

The act of judging or the ability to judge is a delicate matter. Before we are able to judge a situation, we first need to be aware of every fact, every angle of that situation. But, again, it is a delicate matter. We are somehow never quite sure that every angle has been covered. Our instinct and indeed our doubts, can be helpful tools to enable us to assess things.

I believe that the very act of struggling to prove a point is a type of judgment. However, when we do judge, I think it is important that the motivation is for the benefit of others, rather than proving a point for ourselves. By putting our point across, it may improve the quality and ability for all to assess a situation.

While judging through complete understanding may be considered part of the Buddhist path, the development of pure view may be considered as the path within the path.

The higher the level of purity in our view, the lower the burden of having to judge at all. When we have pure view, we are able to see the facts as they are; there is no need to judge or say something is like this or like that. When we have pure view, we do not need to go around struggling to prove something. It is what it is.

As long as we have pure view, there is less room for mistakes, and everything becomes clearer. Questions might arise about whether or not we all have this potential for pure view, but those with pure view understand that we all have this potential. Those with pure view have a very broad—a panoramic—perspective, let’s say. Again, the need to judge, either oneself or others, is no longer present.

Now, when it comes to benefiting others, let’s say in the case of a bodhisattva, the purpose of his or her life is to guide and support others. To be able to do this, you first need to be a good guide yourself. Part of being a good guide is to make things clear for others, which in some ways entails an element of judgment. In the case of a bodhisattva, therefore, some judgment comes into play, even when there is pure view.

Is it true that Buddhists don’t believe in God?

It is a very interesting and important question, and a simple yes/no answer would not suffice. Therefore, a little elaboration is required.

In general, and in simple terms, happiness is what we all seek. It’s in our nature.

Some people doubt whether happiness can be found from within.

Because of these doubts, this confusion, and lack of knowledge, these people look to external sources to find happiness. They try to find happiness, freedom, peace, and enlightenment through divine intervention, for example.

When uncertainties exist, it is somehow easier to project an external source of happiness, rather than look within. Thus, humanity has tried over millennia to find the source of happiness outside ourselves.

With innocent motivations, we have come up with various outer sources of happiness (e.g., religions, anti-religions, power, and money). As we continue to struggle in our external search for happiness, our progress seems to be limited in some way.

What Buddha Shakyamuni suggests is that, while we struggle in our endless search and pursuit for happiness, we forget to ask, “Could it be that happiness is gained from within?”

He brings into focus, for example, the impermanence of all phenomena, like the very experience of “today.” If we truly investigate “today’s” nature, down to the very last fraction of experience, we might find that it never lasts. It is therefore free of a truly existing essence of “today” even though it manifests vividly, and even leads to the experience of “tomorrow.” Today is constantly changing, forever in flux.

If we accept the impermanence of life and nature, we can see how the external search for happiness may face many challenges along the way. A fixed view of “today” may lead to a fear of the day passing into “yesterday,” a fear of “tomorrow,” and so on. When we accept the way things are, perhaps we could liberate ourselves from these fears, and find peace and happiness from within. We might even enjoy this “today” without depending on outer means.

In short, it is very difficult for a Buddhist to claim that there is a belief or doctrine that truly exists because of the idea of impermanence. Therefore, the concept of a creator is not recommended.

Having said that, in Buddhism there is a belief system but it is in the form of a guideline. For example, should the belief in the notion of “karma” (the law of cause and effect) support someone in being a decent person, then that belief is valid, but only within that specific framework. This does not imply that there is such a thing as a fixated karma or a truly existing karma.

When we embrace impermanence and look inside ourselves, we are able to free ourselves from fear and support each other in our universal search for happiness.

Your Holiness, what is stopping me from realizing my true nature, the Buddha nature?

Perhaps it is a lack of a sense of adventure that is holding us back from realizing our true nature. It is easy to get used to the mundane life, the daily routines. As a result, we don’t want to let go of our familiar atmosphere, the life that we are used to. We are missing a sense of adventure.

I think this is rooted in a deep fear: a fear of facing ourselves, a fear of knowing exactly who we are. It is almost like saying we fear looking at ourselves in the mirror and seeing our own reflections.

Of course, the trouble, or rather the challenge, comes from believing that the mundane elements of our lives somehow define who we are. The errors, the mistakes, the hardships, and challenges that we have faced, can sometimes feel like they become a part of us. They hold us back, leaving their mark, sometimes even a sense of trauma. But these experiences are not part of our true nature. In fact, in some ways, they can hold us back from seeing our true selves.

Over the years, this kind of habitual pattern can somehow make us not believe in our own true nature, and feel that it is just wishful thinking that our true nature is different—a hopeful dream! So, I think this is what we have to overcome.

So that’s why we have to have great courage, and be a bit stern, even a bit stubborn, to really face ourselves.

As practitioners, we will all be faced to some degree by the emotions, challenges, and obstacles we experience in life. Without truly facing them, we will never ever realize our true nature.

When we really face ourselves, when we see our true reflections in the mirror, we see that the errors of this life are manifestations of none other than karma and disturbing emotions. We are then able to accept the way things are in quite an efficient way. It is almost as though we are tagging or categorizing our mundane experiences. Once we have somehow put them in their own places, we have nothing to see but ourselves and our true potential. This takes courage. It takes courage to face the fear of the past—to overcome the error of seeing our negative experiences as part of our true selves—but we need to do this in order to help realize our true nature.

Your Holiness, please explain how best a true Buddhist can lead a normal, non-monastic life?

The poem Letter to a Friend by Nagarjuna beautifully sets out some basic guidelines for a non-ordained person to live their life.

But even if all these guidelines were followed, there would still be some challenges. A great deal depends on the individual concerned, their karma, and other factors. For example, some people may have the motivation, but lack the circumstances. Others may have the circumstances, but lack the motivation—in terms of entering ordained life, of course. So it is really a hard thing to say how best to lead a normal life, as everyone is different.

The monastic sangha is crucial to help ensure the buddhadharma’s benefit for all sentient beings. Without it, I would say that it would be very, very difficult for the buddhadharma to flourish. I believe that this was one of the very first reasons why our historical Buddha Shakyamuni established the sangha. I don’t think he intended to develop the monastic system to convert everyone. But should an individual, according to their own aspiration, wish to access the buddhadharma and follow this path, then the sangha enables them to do that.

So there are many helpful guidelines for non-monastic life in Letter to a Friend by Nagarjuna, though one should always be mindful of the benefits and importance of the sangha.

Dear Karmapa, what is the best practice to work with speech in order to make it become Buddha speech?

I like that question. It is quite simple and to the point.

I think a simple answer would be that any speech that comes from a kind heart (in the unemotional sense) would help make it more like Buddha speech.

If someone is a little bit emotionally disturbed and shaken, then the speech expressed may reflect these internal disturbances and this may in turn be confused with a kind heart. A kind heart flows not from emotion, but from a clear conscience. When the conscience is clear, the heart is kind and beneficial speech and activities follow. When the conscience is clear, the speech becomes more like Buddha speech.

I believe that the reason we call it Buddha speech is because there is simply no agenda at all. We can see this from the very sutras that we have; the very teachings and actual words of Buddha reflect this. It is pure generosity. It is genuine sharing, the ultimate form of sharing.

There is a saying that sharing is loving. In this case, the Buddha’s teachings are the perfect example of this. Buddha’s genuine sharing is a reflection of limitless love.

So what are the qualities of Buddha speech? The qualities include: having perfected not only speech, but action and thought over many eons (basically meaning over many, many lifetimes); where there is simply no need for any agenda, as one can see the faults within any kind of agenda; seeing the positive qualities of generosity and kind heart; and, then simply sharing knowledge.

Let me give an example. I think most of you are familiar with the various aspiration prayers. One that comes to my mind is that of the Samantabhadra Aspiration Prayer. It is perfect in every way. There is simply not one sentence—in fact, not one word nor even one syllable—that is not a Buddha speech (unless, of course, it has been wrongly interpreted or written in some way).

Of course, all of the sutras and the teachings of Buddha are examples of Buddha speech. They are perfect because there is no self-interest, agenda, or expectation of something in return. It is pure giving. It is genuine sharing.

Going back to the characteristics of Buddha speech, an important question to ask is if something is beneficial. Speaking about the weather, for example, may not be particularly useful (except in certain circumstances). If speech is beneficial, if it is useful, then it is worth considering. Otherwise, it may be better to leave it. Understanding the context is important, as some things may be beneficial in some cases but useless in others, and vice versa. It is also important to consider how much control we have over our speech, thoughts, and actions—how much composure do we have as an individual?

There are times when one can engage in various speeches, engage in various topics. Whether it is talking about the weather, painting, cooking, baking, sports—whatever—it doesn’t matter so much, as long as it is beneficial.

But what does it mean for speech to be beneficial? From a Buddhist point of view, when we use the term beneficial, it often refers to two things: beneficial in this life and in the next life. Beneficial speech will help us reach liberation and then gain Samyakasambuddaya.

If it helps an individual and others, we can engage in seemingly pointless speech. We can whistle or hum, as long as it is beneficial. Maybe, for some people, they like to hum. Maybe humming is their hobby! Maybe it is their passion. Maybe it is the thing that really makes their day. If they are not able to hum that day, for them it is a bad day. They may not be able to sleep properly or they might have nightmares. For someone like this, it might be helpful to encourage them by humming along with them, to help them reach liberation and enlightenment! You hum a little and you get closer. When you hum twice you can get even closer, and then a little more, to a point where one can maybe have a conversation! Yes, understanding the context and what is truly beneficial is very important.

You can find Karmapa on Facebook at www.facebook.com/theKarmapa.