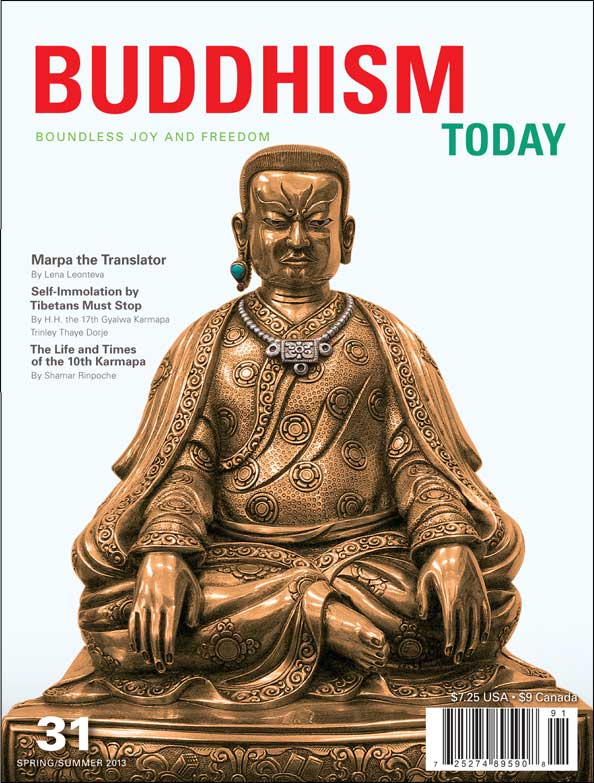

Marpa the Translator

by Lena Leonteva | Issue 31

A religion coming to a new culture is an interesting subject to analyze! There are people who live in their homeland for centuries with their own foundations and traditions. Then a foreign religion enters their space, and soon they accept it.

Marpa translated everything into Tibetan and wrote it down carefully, preparing to bring the treasure to Tibet and transmit it to his fellow countrymen. He was completely sure about the precious value of all the big and small oral transmissions received from famous gurus as well as ordinary practitioners in the caves and graveyards of India.

Some religions are brought, as poets say, by fire and sword. Buddhism has always emerged as an interesting view for the elite. For fifteen hundred years, it was called the “king’s religion.” Sometimes an educated rich person, often a king, would visit a neighboring country where Buddhism was practiced. He or she would learn some Buddhist truths and like it. Upon returning to the homeland, this person would open Buddhist texts, light incense, and practice. After a while, others would start noticing that the person had changed and become easier and more relaxed—fearless, joyful and compassionate—in all situations of life. It would inspire their close associates and their attendants. Interest in the Buddha’s teachings would then spread and go deeper into other layers of the society.

Marpa the Translator belongs to the second wave of the spread of Buddhism in Tibet. The first wave (a king’s wave again), started by King Trisong Detsen and teachers Shantarakshita, Kamalashila and Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) in the eighth century, had bad luck. One hundred years after them, King Langdarma, during only six years of his reign, managed to destroy all Buddhist institutions. The teachings went underground and remained a family transmission for about the following two hundred years. The second wave was a movement from the bottom up where many young heroes from various strata of Tibetan society were brave enough to travel to India and bring the Buddha’s teaching to their motherland.

Marpa was born in 1012 in a fertile valley called Lhodrag in southern Tibet. His parents were wealthy people who owned a mountain slope and ran a farm with many workers. In his childhood, Marpa was a very naughty boy. Later, he wrote in his autobiography, “When being a child, I enjoyed getting drunk and fighting.”1

The whole village was terrified by the young boy. Once his father received a delegation of neighbors saying: “Please do something to calm down your son. If you don’t, all of us had better move to another valley. Otherwise, he will destroy everything here.”

The father took their concerns seriously and found a way to both satisfy them and educate his son. He found a dharma teacher for Marpa far away from their village. The teacher was no simple village lama, but a famous scholar and translator called Drogmi Lotsawa, one of the first teachers of Sakya school of Tibet.

We can see that Marpa was the type of person who did everything fully: whatever he touched, he completed. If he fought, he fought fully. If he drank, he really drank. And if he studied, he studied fully, too. Sent to Drogmi at the age of twelve, he learned everything Drogmi could teach him by the age of fifteen. Understanding that he could not go any deeper into the dharma with his lama, young Marpa decided to go to the roots—to travel to India and find the best teachers ever and learn from them.

One can imagine how difficult such a journey would have been at that time. Tibet is a country of Arctic climate lying at least three thousand meters above sea level. Dangerous snowy mountain passes, about six thousand meters above the sea, stood in Marpa’s way. Wild animals prowled everywhere, and robbers could stop one on every corner. Still, he was so eager to find the Buddha’s precious teachings that he did not care about the dangers. He found a companion called Nyo who was a couple of years older and much richer, and they traveled to India together.

Descending into Nepal, which lies midway from the perspective of altitude and climate, Marpa met two lamas who were students of Indian yogin Naropa.2 We know many names of Indian mahasiddhas from the tantric era, which lasted from the sixth to the twelfth century. Some of them seem to be just legendary people, and some are surely historical. Naropa is definitely a historical person. A traveler named Nagtso Lotsawa who visited India in 1040, probably shortly before Naropa’s death, described him in the journal of his travels. He wrote that Naropa was extremely famous and respected. Even local kings considered it a big blessing to see him and to have him put his foot on their heads. He was “quite corpulent, with his white hair [stained with henna] bright red, and a vermilion turban bound on. He was being carried [on a palanquin] by four men and chewing betel-leaf…”3

Marpa stayed in Nepal for three years learning from Naropa’s students, absorbing whatever teaching and instructions he received, and truly entering Naropa’s mandala. Then, at age nineteen, he continued to India and went straight to Naropa’s place. Some accounts describe the place as a monastery, though, of course, it was not. It was called “Fields Covered with Flowers,” and was definitely not a monastery because there was not a single monk residing and practicing there. It was a retreat center where yogins and yoginis would stay or come to meditate and get teachings from the famous master. Marpa arrived in 1031, so he had nine years to learn from the great mahasiddha before the death of the latter.

During his stay in India, Marpa visited many tantric teachers, receiving their teachings and blessings, practicing, and completing the tantras and meditations he received. He translated everything into Tibetan and wrote it down carefully, preparing to bring the treasure to Tibet and transmit it to his fellow countrymen. He was completely sure about the precious value of all the big and small oral transmissions received from famous gurus as well as ordinary practitioners in the caves and graveyards of India.

Later he said that he had met 108 teachers. We know thirteen names and two of the teachers who were root gurus for Marpa—Naropa and Maitripa. Marpa himself explained why he needed to see so many teachers, saying that, for one non-enlightened student, one enlightened guru is completely enough. He only went to other gurus because Naropa sent him. The great mahasiddha already knew that Buddhism would not survive in India because Muslims were standing on its western borders. Under the slogan of “jihad against infidels,” the Muslims started a holy war in Northern India. Around the year 1000, a warrior king named Mahmud Gaznawy attacked India seventeen times, leaving not a single stone of a Buddhist temple and not a single Buddhist monk alive. That is why Indian mahasiddhas of that time were very open to teaching foreigners, especially Tibetans. They knew that, in the cruel coming years, tantric Buddhism would only survive behind the gigantic snowy walls of the Himalayas.

Naropa knew that the culture of mahasiddhas in India was declining, but that Marpa would become his successor and would start a big and important lineage in Tibet teaching many people. That is why the guru wanted Marpa to meet many Indian mahasiddhas, get acquainted with their various teaching styles, and be free to apply these teaching styles later in his motherland. Marpa did that. Eventually, he collected his writings, said goodbye to Naropa, and started his journey back to the Land of Snow.

His previous companion Nyo was again traveling with him. They had already met several times during Marpa’s stay in India. As men, they would buy a lot of wine and food, meet in a bar, and compete in their dharma knowledge. Marpa always won, which fueled Nyo’s strong jealousy. Now, traveling with Marpa and seeing his big load of Tibetan letters, he thought, “Okay, all his knowledge is here, in his writings. I have only to get rid of the papers, and then I’ll be the greatest scholar of Tibet.”

Marpa

Marpa

When they were crossing the Ganges River in a boat, Nyo secretly asked the boatman to drop Marpa’s books into the water. When Marpa saw that the books were gone, for a moment he experienced strong despair: “Shall I jump into the river and drown together with my texts?” But soon he overcame the disappointment because he knew that his knowledge and wisdom were not in his books, but in his heart. Then he sang a chastising song to Nyo, saying: “How can you call yourself a dharma teacher, when you are so much subject to such a profane feeling as envy? You should now purify yourself, meditating in a retreat!” Still, even if Marpa overcame his resentment with Nyo and was beyond disturbing feelings, he thought, “If I keep traveling with him, I will only accumulate negative emotions.” Then, he separated from his unfortunate companion and made all his later tours to India alone.

Altogether, Marpa traveled to India three times. After the first journey, he started acquiring students in Tibet. He got married several times. His main wife was named Dagmema, which means “A Lady Without Ego.” He had seven sons and several daughters. He opened three study centers and a retreat center, similar to Naropa’s center, in his home valley.

It was a farm where some people worked, some resided and practiced, and others would come for a while to take part in teachings and initiations. He left a huge legacy of translations from Sanskrit into Tibetan: tantra texts, commentaries, poems, and texts on history, logic, philosophy, and practice. He had many students, five of whom became holders of his different transmissions.

In this way Marpa started a transmission lineage that was later called Kagyu: “a lineage of the orally transmitted Word of the Buddha.” This name does not mean that Kagyu tradition neglects written texts. It has had many very famous scholars who have written important multi-volume commentaries and philosophical works, but the priority lies with oral transmission, as has been traditional since the Buddha’s time. The true teaching and experience is purely transmitted only by a living person who has practiced the teaching and realized it. Through meeting such a person, one gets not only the words of the dharma, but also an experience of it and a blessing. In Tibet, many teachings were not allowed to be written down. One cannot find them in books. One can only receive them personally from a qualified teacher— from mouth to ear. This way of teaching appears to fit very well with the minds of Tibetans, who are wild and strong warriors willing to get straight to the point.

When analyzing various life stories of Marpa the Translator written by different authors, one finds many discrepancies in dates and events. Upon investigation, one can make several discoveries. Among these is that Marpa left India in 1038, probably after a stay of six years while Naropa was still alive. His main guru Naropa died in 1040, but Marpa, unaware of this, went there for the second time, in approximately 1049. Then he heard very sad news about Naropa “entering the stage of action,” which Lama Ole explains as Naropa’s death4. It is interesting that only one of Marpa’s early biographers had the same idea. It was Gö Lotsāwa Zhönnu Pal, the author of Blue Annals. Zhönnu Pal suggested that this expression means death. This would mean that Naropa had long been dead when Marpa came to India for the second time. Marpa searched for his beloved guru for a long while, and finally met Naropa’s power field, or his light body—the Joy State. This means that Marpa was already on high bodhisattva levels and could communicate with buddhas in their light and energy forms.

Here, on their second meeting, a very significant event for the whole Kagyu lineage happened. Naropa, in his Joy State, being next to Marpa, created a light and energy form of Hevajra, Marpa’s personal meditational Buddha-form, in the sky. Marpa was, of course, very impressed. “Who would you greet first,” Naropa asked, “him or me?” Marpa, following a strange inner push, bowed down in front of the yidam, and Naropa then said, “It’s a mistake! For us, the teacher is the most important!”

So Marpa made a mistake. Then he had a difficult time and was very sick. He was almost dying, sometimes losing consciousness, and often thinking: “Well, I’ve been a lama for at least ten years. I’ve always known that all yidams are emanations of the teacher. I have taught all my students the same. So, why did I greet Hevajra instead of Naropa? That must have been a purification of an old former mistake, from past lifetimes.” Thinking this, he was lying in bed, surrounded by his dharma brothers and sisters. They were quietly discussing how they could cure him—whether they should call this or that doctor or buy this or that medicine. Hearing this, Marpa said: “Dear Vajra brothers and sisters! Whether I live or die depends purely on the karma of Tibetans. If they have the good karma to receive the teachings I am about to bring them, I will survive anyway, whether I get proper medicine or not. And if they do not have this karma, I will die anyway, however well you try to cure me. So, let us not spend money of the sangha and rely on the nature of phenomena!”

Marpa soon recovered from his disease, which was the sign of Tibetans having a lot of good karma (like we have now in the West). Then they had a farewell meeting with Naropa, and Marpa wanted his guru to pronounce prophesies about the future of Marpa’s transmission lineage. The issue of monastic or lay lifestyle, which had been preoccupying Buddhist practitioners since the time of the Buddha, was a worry for him, as he was definitely not a monk. He loved women and drank alcohol; he was engaged in all the pleasures of life. So he asked Naropa, “Should I take monks’ vows and demand the same of my followers?” Naropa kindly replied: “You do not have to do this, as your desires are so obvious, as if being carved in stone. As for your followers, in the future of your lineage there will be people who will wear monk’s robes, and there will be other practitioners of various appearances, but all of them will make your lineage spread and blossom. You can enjoy all pleasures of life, but you are not caught by them.”

Marpa made his last journey to India when he was more than sixty years old. He did it alone, and now one can ask: why did he need to go there again? His root teacher had been long dead! Analyzing various life stories of Marpa, one can make the following conclusion: he went there to meet Maitripa. As an experienced dharma practitioner, Marpa knew that one should have a living root teacher. Naropa was dead, but there was Maitripa, very famous for his Mahamudra transmission, and himself a student of Naropa, which made his accomplishment very reliable and pure.

Also, looking at the entire collection of Marpa’s works, one can see that they include multiple translations of various works of Tilopa, Naropa, Saraha, Kukkuripa, Dharikapa and other mahasiddhas, but only one translation of Maitripa’s work. This may mean that Marpa met Maitripa very late in his life, when he was already a well-known teacher and no longer engaged in translations. Modern scholars date Maitripa’s birth to either 995 or 1007. Both dates show that he was quite young when Marpa traveled to India for the first and second times. So, the most convincing explanation is that Marpa met him on his third and last journey. He received the Mahamudra transmission and returned to Tibet carrying the deepest and most important teaching originating from the Buddha and transmitted in India of that time.

The works of Marpa show his deep devotion to his teachers and to the view of the Diamond Way. It’s only in Marpa’s books that one can read about the union of bliss and emptiness; other lamas do not touch this subtle (and secret) point in their writings. Over about one thousand pages of his works, Marpa mentions Mahayana themes, such as the Paramitas, only a few times and always in order to point out that the Mahayana way takes three immeasurable kalpas. In contrast, the Diamond Way can bring one to enlightenment in only one lifetime. Marpa does not bother himself with explaining a gradual way to the Buddha’s state. His main purpose is to present his capable disciples with the advantages of the immediate path—the way of Tantra and the Great Seal—which requires devotion and highest view, and can quickly transform one’s ordinary mind into the mind of a Buddha.

1 rje mar pa’i rnam thar // Bri gung bka’ brgyud chos mdzod, Ca. Xylograph (Lhasa: Tibet People’s Publishing House, 2004), pp. 167-168.

2 Naropa’s dates of 1016–1100 as given in some accounts are obviously wrong. He could not be younger than Marpa, so many scholars accept earlier dates: 956–1040.

3 Ronald M. Davidson, Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 339.

4 George Roerich, Blue Annals (Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1949), p. 402.